Description

| Position | Title/Credits | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Listen To Me | 6:41 |

| A2 | Mama Get Yourself Together | 6:15 |

| A3 | A Change Is Going To Come | 9:31 |

| A4 | Aquarius | 4:56 |

| B1 | Mighty Mighty | 2:49 |

| B2 | Hard Times | 3:23 |

| B3 | California Dreaming | 4:48 |

| B4 | Running | 3:39 |

| B5 | One Dragon Two Dragon | 4:03 |

| B6 | You Make Me So Very Happy | 1:51 |

| B7 | Little Linda Turn On | 3:14 |

| B8 | Turn On To Me | 3:28 |

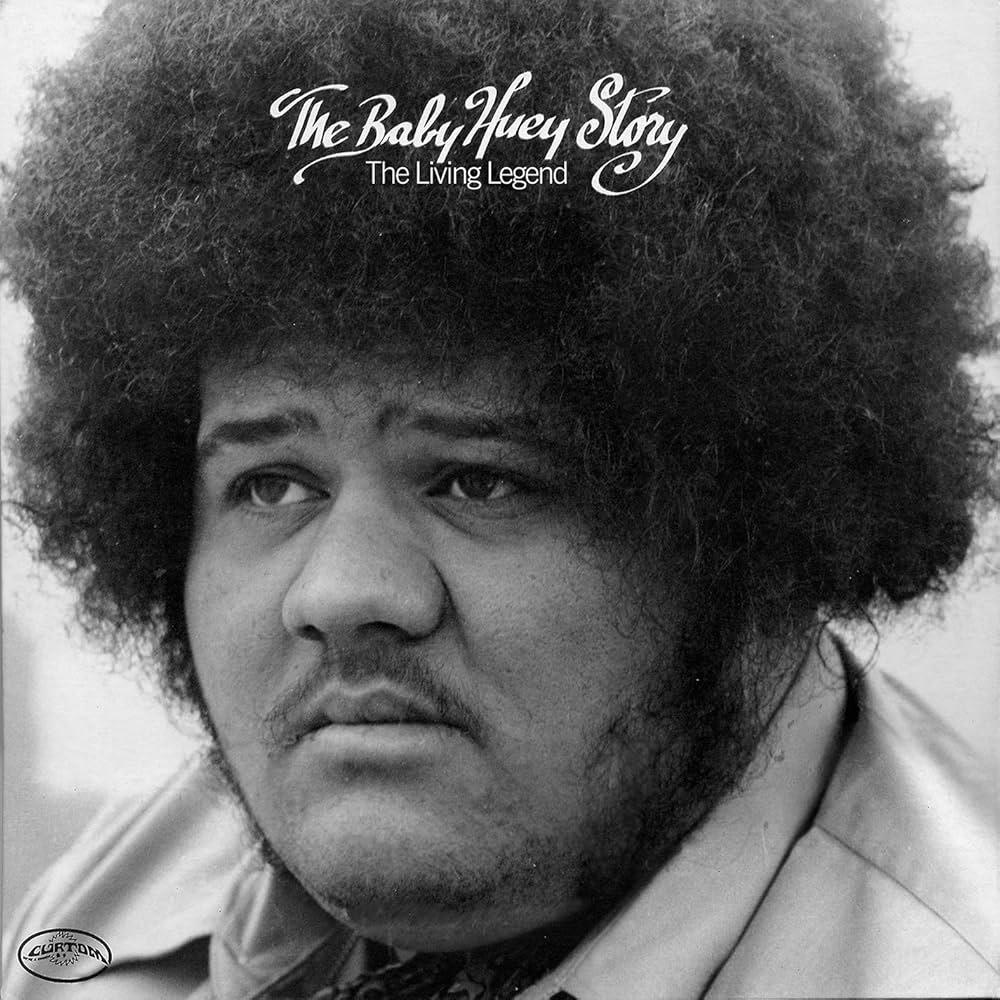

James “Baby Huey” Ramey is a stark example of an artist that burned bright and fast. The Living Legend: The Baby Huey Story features music stunningly vibrant and electric. And yet it’s represents the vast majority of what he was able to record and share with the world. Posthumously released 50 years ago, it stands as a monument to something that could have been but never was. It gives the glimpse of the unique individual who, at the time of his death at the age of 26, was only beginning to realize his musical potential before his life was extinguished.

Over the last half a century, Living Legend has achieved, well, legendary status. Curtis Mayfield produced the album in its entirety and released it on Curtom Records, his label. It was not a hit at the time, and its lack of commercial success made it a rarity. Like all the best “cult classics,” it’s a powerful and soulful album, crafted by singular talents, that wasn’t appreciated during its time.

When I first began digging for old soul records around 2000, Living Legend became one of the first albums that I really coveted. I dug through many a dusty crate, even after learning that most copies went for $50 to $75 at the time. I eventually bought a vinyl repressing, and it quickly became a personal favorite. A year or so later, I found an original for $11.95. It’s not in the best condition, but I’m still very happy to have an O.G. copy.

Living Legend isn’t just sought after because it’s rare; it’s a formidable piece of musical work. It only contains eight songs, three of which are instrumental, but you could definitely tell that Ramey had a star quality. His vocals were resonant, and his personality is apparent on every track where he sings. He brings his exceptional sensibilities to both original material and soul music standards.

Ramey was a distinctive artist with a distinctive look. Due to a glandular condition, he was always a large, heavy-set individual, eventually growing to 6’2” and topping 350 pounds. This indeed earned him the nickname that he shared with the cartoon duck, the latter best known for his oversized stature and child-like nature and attire.

Ramey hailed from Richmond, Indiana, a town where people used outdoor plumbing and “brothers wearing pointed-toe shoes and carrying 45s” were a common sight. However, it wasn’t until he moved 250 miles away to Chicago in 1963 that he really gained attention as a singer.

Ramey formed the Babysitters soon after moving to Chicago. They worked to hone their stage show, one that was heavy with Beatles covers and Motown hits, and punctuated by Ramey’s ability to communicate and connect with his audience. Eventually, they found a home at the Thumb’s Up club in the cities North Side, where strong word of mouth soon produced beyond capacity crowds whenever they graced the stage.

Over those first few years, the Babysitters’ membership swelled from four to ten, and they became a huge attraction throughout the city, often playing seven nights a week. The band earned a reputation not only for their prowess on stage, but for their willingness to play anywhere and everywhere. Renown artists visiting from out of town (or even out of country) would make sure to catch the Babysitters’ live show. Along the way, the group also recorded a few 45 RPMs on small, independent labels.

As the band grew in popularity, the Babysitters found new opportunities. They performed in Paris for a month. They hit the west coast talk show circuit, performing on Merv Griffin and Michael Douglas’ respective programs. And as the times changed, Ramey began to embrace the hippie aesthetic. He traded natty suits and satin baseball jackets for African robes and Kente cloth, and grew out an afro.

Around that time, Baby Huey and the Babysitters came to the attention of Curtis Mayfield and Curtom Records. Label A&R and future solo artist Donny Hathaway caught a live show and was completely sold on the group. The label signed Ramey, and only Ramey, to a contract, with Mayfield deciding that he was the main attraction.

Unfortunately, trouble began for Ramey during the process of recording an album. His weight swelled to 400 pounds. He began drinking too much and, since this was late ’60s/early ’70s, picked up a drug habit; heroin, to be exact. He entered rehab, but it didn’t take. On October 28, 1970, he was found dead in his apartment. His death was initially announced as natural causes, but was later listed listed a heart attack, brought about by his weight and drug use.

Living Legend’s sole attempt to really capture Ramey’s early days is with the album’s first single, “Mighty, Mighty.” The song is a cover of one of The Impressions’ earliest hits, and Ramey and crew do it justice. Part 1/Side A of the 45 RPM is a reasonably straightforward, albeit more boisterous cover of the song. Ramey flips some of the lyrics around, occasionally incorporating “Baby Huey” and changing “Mighty Mighty, spade and whitey” to “Mighty Mighty children, unite yourself with power!” The song was a hit, with the 45 selling 200,000 copies.

However, only Pt. 2 of the song appears on the initial pressings of Living Legend. Here, they try to recreate a live performance of the song, with Ramey’s riffing to the audience serving as the song’s attraction. It’s certainly an enjoyable approach, giving the listeners the impression of a Baby Huey live show. Ramey continuously banters, recalling eating “turkey dinners and them dressings” on the street where Lou Rawls grew up, and proclaims that Thunderbird is the word. Even though I doubt he recorded it in front of a crowd of a 1,000 people (as Ramey states), his energy is impossible to deny.

“Listen To Me,” which opens the album, radiates with a vitality that echoes to Sly and the Family Stone’s “I Want to Take You Higher.” The horn section bellows as Huey lets of out mammoth shouts and wails, wringing ever ounce of emotion out of his soul. The song is short on lyrical cohesion, but long on visceral excitement.

Mayfield pens two other songs on Living Legend. The first is “Hard Times,” where Ramey and crew find the way to strike the right balance between creating an atmosphere that’s dire, but still musically luminous. The song grips you within the first five seconds, opening with haunting keys and a pounding bassline, followed by brief licks of guitar.

Ramey’s vocals convey his despair, as he describes living in abject poverty. He’s both fearful of his surroundings and reacting to the fear of others that he observes in his own interactions with his fellow ghetto residents. The horn section blares as he recollects sleeping on hotels floors and subsisting on Oreos and SPAM. It’s the album’s most evocative entry. Mayfield would later cover the song on There’s No Place Like America Today (1975), transforming it into a moody, bluesy meditation. While Mayfield’s take is great its own right, Baby Huey’s version towers above all.

“Running,” another superior Mayfield-penned entry, finds Ramey assuming the role of an “educated fool” driven mad by love, chasing the object of his obsession. Furiously in pursuit of a woman who’s left him for someone else, Huey’s vocal are charged with pain and anguish, carrying the mind-bending instrumentation to another level.

To add to Ramey’s hippie bonafides, Living Legend features him performing a nine and a half minute, psychedelic version of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come.” Ramey powers through the classic, his voice surging with passion, layered in echoing reverb, meeting the bombast of the soaring horns and expert organ playing. But what really gives this version its character is Ramey’s three and half minute ending soliloquy. He reminisces about his formative days in Indiana, waxing philosophic about drinking wine and “taking care of business at the drive-in movies.” He describes how smoking “one of those funny looking cigarettes” provided him with the ability to center himself mentally. He completes his sermon by declaring the three types of people in the world: “I say there’s white people, there’s Black people, and then there’s my people.”

Ramey’s cover of “California Dreamin’” is less successful, as it doesn’t add much to the recording. It’s one of three instrumental songs on the album. Ramey himself penned the other two, “Mama, Get Yourself Together” and “One Dragon, Two Dragon.” The former is stronger, channeling the vibe of Archie Bell and the Drells and other soul outfits of the era. “One Dragon…” is solid but unspectacular. I suspect it was originally written a vocal track, with flutist Othello Anderson taking the place what I imagine would be a passionate performance by Ramey.

The liner notes for Living Legend feature many newspaper clips about Ramey’s death. A few lean heavily into relating his death to those of Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix (Ramey was friends with the latter), as all three died over the space of a little over a month. There’s also a lengthy note from his manager, Marv Stuart (aka Marv Heiman), who eulogizes his friend. “I knew him as a very real person and not another puppet to be dangled on a stage,” Stuart writes. “He said what he felt and truly felt everything that he said.”

A half a century after its initial release, Living Legend isn’t quite as underappreciated as it used to be. It’s been frequently rediscovered by crate diggers and music aficionados alike. Each time it get re-released (mostly on vinyl) it receives a new round of press. It’s currently available on most streaming sites, along with an “expanded version” of the long-player. “Hard Times” has been featured in an episode of Atlanta, as well as used as the theme music for the first season of the Conviction podcast and the Fear City TV show.

We, of course, will never know if Ramey could have achieved the status of cultural icon like Hendrix and Joplin if he lived a few more years to build his musical catalogue. All we have to go on is a few scattered 45 RPMs and Living Legend, which while outstanding, in some ways feels incomplete. But from listening to the what Ramey was able to record before he died, you can certainly hear what Mayfield saw in him. Ramey had it in him to became a full-fledged star, and it’s a shame that we never got to see make that transition.

Jesse Ducker

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.